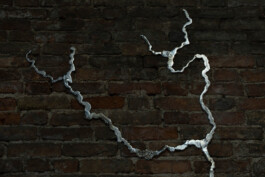

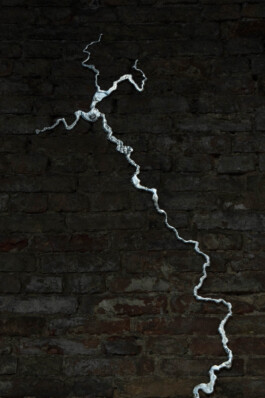

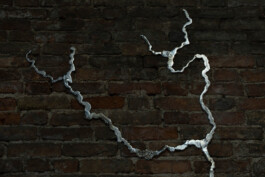

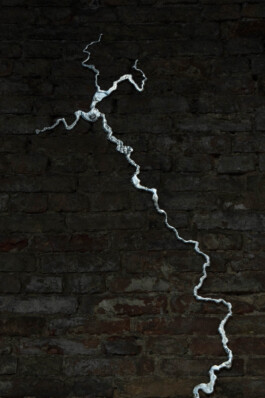

Suture: staging the scars

Venice Arsenale

2024

tin

Our skin is a surface. A surface which changes with time - the cracks on it are the indelible mark of happenings, of time imprinting itself on our bodies. As I age, cracks - their very essence as tactile evidence of lost (or found) time - have fascinated me. I am a person who ages, whose skin cracks as time moves forward. But as my skin cracks, it leaves a trace of the past in the present, a physical manifestation of living memory.

A wall, like our skin, has a living memory. A sudden, intense blow can create a crack, or slowly a fracture can form as pieces tumble - but the living memory of those pieces remains - despite their absence, the trace of their presence lingers. Sutures allow our wounds to heal, for cracks to connect, but we will always wear the scars of time, and must not forget where they came from.

If a crack is a wound, how can we use them to help us heal the wounds of history? The question is not to look away from the cracks, but to find them, to remember them, and by remembering them, imagine alternative futures.

'Nothing is created, nothing is destroyed, everything is transformed’. - Lavoisier's Law

The Arsenale was the largest production centre of the pre-industrial era, a vast complex of shipyards and armouries that produced both merchant and war fleets. The furnaces beside us were once used for melting metals, including bronze - a quintessential metal in sculpture. But sculptures were not made here, armaments were - and as with all industry, the trace of violence - the structures of power required to build the Venetian Republic - can be found in this room, in its cracks.

For this century's old wall, the supporting sections of Suture have been shaped by following the constellation of interstices that have opened over time between the bricks - those areas where, over the years the mortar has dried and crumbled, creating fissures.

I first encountered tin when I read about the liquidation of an elderly tinsmith’s workshop; he was selling off his remaining metal and tools. I acquired large tin bars he had used for soldering electrical circuits, and among his tools, I was struck by a small, heavy, and reliable electric crucible from the 1950s, which I still use today. Even now, I search for and collect reclaimed tin rather than newly mined material. The tin I use, therefore, carries with it a history of previous uses, and through an endless process of melting and solidifying, I shape it in response to each installation context. The day Suture loses its identity as a work of art, the tin will immediately be available for a different use.

When I began working with this metal, I was immediately fascinated by its resistance to air and water and its ease in shifting between solid and liquid states. With my roots in graffiti, I quickly wanted to test it by taking it to the streets. Cities contain many spontaneous moulds, and tin adapted well, especially to the cracks in the ground. As I worked with it, I soon discovered that, when melted and poured by hand, tin could take a shape very similar to that of a fissure. From that moment, I decided to move beyond mere traces of reality to involve fiction, to engage in the act of staging. I represent an invented crack, staging the passage of tomorrow's time to wonder at possible futures.

Suture: staging the scars

Venice Arsenale, 2024, tin

Our skin is a surface. A surface which changes with time - the cracks on it are the indelible mark of happenings, of time imprinting itself on our bodies. As I age, cracks - their very essence as tactile evidence of lost (or found) time - have fascinated me. I am a person who ages, whose skin cracks as time moves forward. But as my skin cracks, it leaves a trace of the past in the present, a physical manifestation of living memory.

A wall, like our skin, has a living memory. A sudden, intense blow can create a crack, or slowly a fracture can form as pieces tumble - but the living memory of those pieces remains - despite their absence, the trace of their presence lingers. Sutures allow our wounds to heal, for cracks to connect, but we will always wear the scars of time, and must not forget where they came from.

If a crack is a wound, how can we use them to help us heal the wounds of history? The question is not to look away from the cracks, but to find them, to remember them, and by remembering them, imagine alternative futures.

'Nothing is created, nothing is destroyed, everything is transformed’. - Lavoisier's Law

The Arsenale was the largest production centre of the pre-industrial era, a vast complex of shipyards and armouries that produced both merchant and war fleets. The furnaces beside us were once used for melting metals, including bronze - a quintessential metal in sculpture. But sculptures were not made here, armaments were - and as with all industry, the trace of violence - the structures of power required to build the Venetian Republic - can be found in this room, in its cracks.

For this century's old wall, the supporting sections of Suture have been shaped by following the constellation of interstices that have opened over time between the bricks - those areas where, over the years the mortar has dried and crumbled, creating fissures.

I first encountered tin when I read about the liquidation of an elderly tinsmith’s workshop; he was selling off his remaining metal and tools. I acquired large tin bars he had used for soldering electrical circuits, and among his tools, I was struck by a small, heavy, and reliable electric crucible from the 1950s, which I still use today. Even now, I search for and collect reclaimed tin rather than newly mined material. The tin I use, therefore, carries with it a history of previous uses, and through an endless process of melting and solidifying, I shape it in response to each installation context. The day Suture loses its identity as a work of art, the tin will immediately be available for a different use.

When I began working with this metal, I was immediately fascinated by its resistance to air and water and its ease in shifting between solid and liquid states. With my roots in graffiti, I quickly wanted to test it by taking it to the streets. Cities contain many spontaneous moulds, and tin adapted well, especially to the cracks in the ground. As I worked with it, I soon discovered that, when melted and poured by hand, tin could take a shape very similar to that of a fissure. From that moment, I decided to move beyond mere traces of reality to involve fiction, to engage in the act of staging. I represent an invented crack, staging the passage of tomorrow's time to wonder at possible futures.